Rebalancing

Imagine you start with a $10,000 portfolio split 50/50 between stocks and cash ($5,000 in each). After a while, stocks go up, cash stays flat, and now you’ve got $7,000 in stocks and $5,000 in cash. Stocks are now 8.3% off their target 50% weight (7/12 - 0.5). Rebalancing means selling $1,000 of stocks and moving it to cash to get back to your 50/50 plan.

Rebalancing is a risk management strategy: according to investopedia, “Rebalancing enables investors to ensure that their portfolio remains aligned with their intended risk profile.”. One can do it in two main ways:

On a schedule (like monthly or yearly), or

Using “bands” - rebalancing only when allocations drift too far (like 5% or 10%) from your target, or

when the trade is large enough - say, over 10% of the asset value (personal preference)

There’s no perfect method. Timing and frequency matter and there is indeed something called rebalancing luck. There are even research papers on this subject.

The questions this post addresses are:

How much does the stock need to rise or fall to trigger a rebalance?

What would be the trading amount?

knowing this helps one plan ahead: e.g. set limit orders, automate trades, and avoid watching the market constantly.

Let’s walk through some basic math. Assume a portfolio with two assets: a volatile one (say stocks) and a stable one (say cash). Let:

C be the total capital,

w the target stock allocation,

b the rebalancing band, and

r the required stock return to trigger rebalancing

Further assume cash stays constant and let C = $1 (it actually cancels out in the calculation of r).

After a return r, the new stock value becomes w(1 + r). Since the cash portion remains at 1 - w, the new portfolio value is (1 - w) + w(1 + r) and the updated stock weight is therefore:

So if the new stock weight drifted from the target weight by b, solving for r in:

results in:

Now that we’ve determined how much the stock can rise or fall before triggering a rebalance, the next step is to calculate the trading amount, i.e. buy/sell order sizing. In the earlier example, it was simply: $7,000 - (0.5 × $12,000) = $1,000.

In other words: Trading Amount = New stock value − (Target stock weight × New total portfolio value). And when expressed in terms of C, w, r, and b, the trading amount becomes:

After simplifying, the amount to buy/sell upon a rebalance:

We can put this to some testing using different stock target weights and bands. For example, in a 60/40 portfolio, stocks would have to fall by 33.33% to trigger a rebalancing buy. The buy amount would be $800 assuming a $10,000 portfolio:

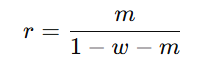

The calculations above assume rebalancing is triggered by crossing predefined bands. Personally, I prefer to rebalance only when the trade size is significant enough - specifically, when it reaches a certain percentage of the stock value (e.g. 5% or 10% of stock value). So, shifting focus, I’ll now calculate the return r that would cause the trading amount to meet or exceed a minimum threshold m, defined as a percentage of the stock value. This reduces the problem to solving for r in the following equation:

which leads to:

Below are a few examples of how much stocks would need to rise or fall to trigger a rebalance based on a minimum trading amount threshold:

It’s also helpful to express m in terms of b (and vice versa), as this allows us to answer questions like: what percentage of the stock would need to be traded if b=±5%? To find out, we need to solve for m in the following equation:

which comes to:

Below are a few illustrative cases. Note that a negative value for m implies a buy. For instance, in a 50/50 stock/cash portfolio, a 5% rebalancing band corresponds to trading amounts of 9.09% (sell) and -11.11% (buy) relative to the stock value. In comparison, in a 60/40 portfolio, a 10% rebalancing band corresponds to trading amounts of 14.29% (sell) and -20% (buy) relative to the stock value: